THE IMPORTANCE OF SANITATION

Key facts (WHO )

- In 2022, 57% of the global population (4.6 billion people) used a safely managed sanitation service.

- Over 1.5 billion people still do not have basic sanitation services, such as private toilets or latrines.

- Of these, 419 million still defecate in the open, for example in street gutters, behind bushes or into open bodies of water.

- In 2020, 44% of the household wastewater generated globally was discharged without safe treatment.

- At least 10% of the world's population is thought to consume food irrigated by wastewater.

- Poor sanitation reduces human well-being, social and economic development due to impacts such as anxiety, risk of sexual assault, and lost opportunities for education and work.

- Poor sanitation is linked to transmission of diarrhoeal diseases such as cholera and dysentery, as well as typhoid, intestinal worm infections and polio. It exacerbates stunting and contributes to the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

Overview

According to the latest WASH-related burden of disease estimates, 1.4 million people die each year because of inadequate drinking-water, sanitation and hygiene. Most of these deaths are in low- and middle-income countries. Unsafe sanitation accounts for 564,000 of these deaths, largely from diarrhoeal disease, and it is a major factor in several neglected tropical diseases, including intestinal worms, schistosomiasis and trachoma. Poor sanitation also contributes to malnutrition.

In 2022, 57% of the global population (4.6 billion people) used a safely managed sanitation service; 33% (2.7 billion people) used private sanitation facilities connected to sewers from which wastewater was treated; 21% (1.7 billion people) used toilets or latrines where excreta were safely disposed of in situ and 88% of the world’s population (7.2 billion people) used at least a basic sanitation service. Diarrhoea remains a major killer but is largely preventable. Better water, sanitation, and hygiene could prevent the deaths among children aged under 5 years, 395,000 in the year 2019.

Open defecation perpetuates a vicious cycle of disease and poverty. The countries where open defection is most widespread have the highest number of deaths of children aged under 5 years as well as the highest levels of malnutrition and poverty, and big disparities of wealth.

Benefits of improving sanitation

Benefits of improved sanitation extend well beyond reducing the risk of diarrhoea. These include:

- Reducing the spread of intestinal worms, schistosomiasis and trachoma, which are neglected tropical diseases that cause suffering for millions;

- Reducing the severity and impact of malnutrition;

- Promoting dignity and boosting safety, particularly among women and girls;

- Promoting school attendance: girls’ school attendance is particularly boosted by the provision of separate sanitary facilities;

- Reducing the spread of antimicrobial resistance;

- Potential safe recovery of water, nutrients and renewable energy from wastewater and sludge; and

- Potential to increase overall community resilience to climate shocks, for example through safe use of wastewater for irrigation to mitigate water scarcity.

A WHO study in 2012 calculated that for every US$ 1 invested in sanitation, there was a return of US$ 5.50 in lower health costs, more productivity and fewer premature deaths. In our work with SIMAVI on Flores in 2015, we found that the costs involved in 3 occurrences of diarrhoea equalled the investment in 1 improved latrine.

Challenges

In 2013, the UN Deputy Secretary-General issued a call to action on sanitation that included the elimination of open defecation by 2025. The world is on track to eliminate open defecation by 2030, if not by 2025, but historical rates of progress would need to double for the world to achieve universal coverage with basic sanitation services by 2030. To achieve universal safely managed services, rates would need to increase five-fold.

The situation in urban areas, particularly in dense, low income and informal areas, is a growing challenge as sewerage is precarious or non-existent, space for toilets is at a premium, poorly designed and managed pits and septic tanks contaminate open drains and groundwater and services for faecal sludge removal are unavailable or unaffordable. Inequalities are compounded when sewage discharged into storm drains and waterways pollutes poorer low-lowing areas of cities. The effects of climate change – floods, water scarcity and droughts, and sea level rise – is setting back progress for the billions of people without safely managed services and threatens to undermine existing services if they are not made more resilient.

Wastewater and sludge are increasingly seen as a valuable resource in the circular economy that can provide reliable water and nutrients for food production and recovered energy in various forms. In fact, use of wastewater and sludge is already commonplace, but much is used unsafely without adequate treatment, controls on use or regulatory oversight. Safe use that prevents transmission of excreta-related disease is vital to reduce harms and maximize beneficial use of wastewater and sludge.

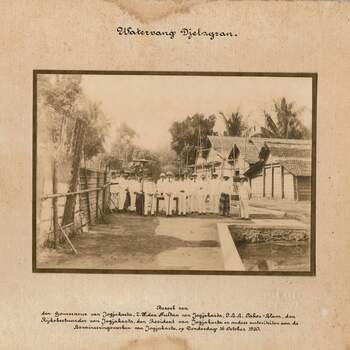

SANITATION IN THIS TIMELINE

In this timeline we deal with onsite sanitation: this refers to systems where urine and faeces is being produced, stored and partially treated. Hence, we do NOT deal with piped solutions such as sewerage. To function properly and to be a ‘healthy’ system, a sequence of interlinking steps is required:

- The temporary storage of faeces, urine, cleansing material and wash water

- Emptying of the facility

- Transport of collected faecal sludge (= mixture of faeces, urine, cleansing material and water)

- Treatment of faecal sludge

- If required: valorisation or reuse of treated faecal sludge

Hence, we don NOT deal with:

- Shallow sewers

- Small bore sewers

- Decentralised systems

- Etc.

A collection of publications of Sjaak van der Geest where he describes the situation in Ghana.

The last taboo examines the history of sanitary reform, and describes the innovative work undertaken by public health engineers and experts all over the world, including those working at the community level whose efforts have been essential to the progress made over recent years. The authors pay particular attention to the impact of sanitation on children’s health, and on the role that children can play in improving their circumstances and those of their families and communities.

One fly is deadlier than 1000 tigers describes a new approach called "total sanitation" which has three pillars :

- it considers latrine users as "clients" with different needs, instead of employing top-down concepts, providing one type of latrine for all,

- It stimulates a thriving private sector to produce and sell latrines as a business, andI

- it stimulates demand with intelligent social mobilisation so that the villagers "awaken" themselves and exercise the social pressure needed to make changes happen.

Interview Dick van Ginhoven Ministry of Foreign Affairs

In this interview, held in April 2024, Mr. Dick Van Ginhoven explains the role of the Government of the Netherlands in the sanitation arena.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

The timeline has been prepared by Jan Spit (1956). Jan is focussing on sanitation, wastewater and faecal sludge management. He was educated as a Sanitary Engineer at the Technical University in Delft (1982, Civil Engineering), completed a post-graduate course on Business Administration in 1999 and became Master Practitioner NLP in 2004. Jan is a self-employed consultant, working for different organisations such as WaterWorX in Kenya and WSUP in Zambia. Other projects include the Lake Victoria Basin Integrated Water Resource Management Programme with High Priority Investments in Kenya. On behalf of WASTE, Jan led the Emergency Sanitation projects with IFRC and OXFAM, funded by USAID (OFDA) and the EU (S (P) EEDKITS). From 2005-2010, Jan was project manager / technical leader at MWH Northern Europe (Previously Syncera, now part of Stantec) and responsible for the development of the field of urban water management and the coaching of staff. From 2001 to 2005 Jan was Programme Advisor at the Netherlands Agency for Innovation, Energy and Environment, in charge of programmes to promote sustainable development at municipality level. Previously Jan was Head of the Planning Department of the Water Utility "Noord-West-Brabant" (WNWB) and consulting engineer at IWACO in Indonesia and India. Jan started as Civil Engineer/Public Health Engineer in Tanzania and Comoro Islands through the United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (UN-Habitat, Nairobi).