NRW in figures

A recent study estimates that the global volume of NRW is about 126 billion cubic metres per year, which, using a conservative value of US$ 0.31 per cubic metre, represent a revenue loss of USD 39 billion per year. This is not only a financial concern, but elevated NRW also detracts water utilities, in a time of increasing scarcity and climate change, from reaching the goal of full service coverage at an affordable price.

In the case of Kenya, in 2018 only 2% of the water utilities operate within the benchmark, i.e. have an NRW less than 20%. The average NRW by all Kenyan operators is 41%. To drive the message on the excessive NRW home, the Kenyan regulator also expresses NRW in volume of water lost (90 million m3/yr), the monetary equivalent of the losses (US$ 70 million/yr) and in terms of losses per connection per day (400 liters). To address the issue, the regulator incentivizes the Kenyan water utilities by making the indexation of their tariff conditional to the successful reduction of NRW (and the reduction of personnel cost).

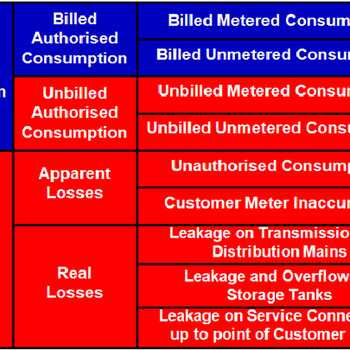

Water Balance

For the determination of NRW, the International Water Associated (IWA) has developed a standard water balance that allows a uniform approach to the analysis of NRW. In addition, there are now 12 freely available software tools (one of them by AWWA, the American Water Works Association) for water balance establisment, NRW performance assessment and NRW reduction planning. A review of these tools (2020) concludes that where they deal well with real losses, they fall short on the assessment and reduction of apparent losses.

NRW investigations using the IWA water balance that have been conducted show quite a variety in NRW, not only in the absolute numbers but also between the main categories of apparent and real losses. In Kenya, nine water providers were investigated in 2017. The results show that total NRW varied between 34 and 77% for the nine companies, with real losses being the dominant component. Among the nine companies, the real losses were between 18.2 and 66.4% and the apparent losses varied between 0 and 23%. In a recent study of one provider in Muscat these two categories are about the same. This brings out the point that measures to reduce NRW must be tailored to the specific, local situation and to the (financial) resources available.

Apart from establishing NRW levels, the above study of Kenyan water utilities also assessed their capacity and performance in six areas covering 18 aspects of NRW management. The analysis shows that here is ample scope for improvement and mutual learning between the nine utilities. However, not one company shows (a more than) satisfactory performance on all aspects. Best practices are in place on six of 18 aspects only, showing a need to look for these elsewhere, possibly at other Kenyan or foreign water companies. Among the six, the better performing areas are those of ‘Customer Metering’ and ‘Other interventions’, and the least performing ones are ‘Active Leakage Control’ and ‘Water Balance, Flow and Pressure Monitoring and Mapping’. This ties in well with the finding that physical losses constitute the larger part of NRW. The study proposes recommendations tailored to each WSP that include a.o. the establishment of NRW teams with specific assignments, the replacement/ installation of bulk meters and consumer meters, operationalisation of DMA’s, pressure management, capacity building.

Aims, measures and results in reducing NRW

Policies to reduce NRW may aim at achieving a minimum (unavoidable) percentage of NRW (saving water) or at arriving at the optimal economic level of NRW (progressive reduction of NRW will become ever costlier). Reduction of NRW is often a costly and time consuming operation that may be hindered by lack of financial resources, the complexity of NRW due to the multiplicity of its possible causes, and furthermore may be counteracted by those benefitting from the status quo. For this reason a thorough analysis needs to precede anything but the most obvious measures.

Measures to reduce NRW are, among others, the following:

General

- Raising awareness on NRW with regulators, providers and the public

- Establish the NRW baseline value

- Conduct NRW studies to inform the development of effective NRW reduction plans

- Setting benchmarks, objectives, targets and incentives for NRW reduction

- Establish, capacitate and resource a dedicated NRW unit

Reduction of real/physical losses

- Network modelling

- District Metered Areas

- Pressure reducing policy and equipment

- Repair visible leakages

- Pipe location and Leakage detection equipment

- Pipe replacement and rehabilitation

- Encourage citizens to report leakage

- Reduction of utility response time to leaks

Reduction apparent/commercial losses

- Customer and meter survey in GIS, and integration with the MIS system for billing

- Verify all disconnected, dormant and ‘gate-locked’ connections

- Conduct Minimum Night Flow measurements

- Rotate meter readers

- Establish a meter testing and repair workshop

- Test and calibrate all production and district meters

- Replace/install bulk meters, DMA meters and customer water meters

- Introduce smart meters and automated meter reading

Examples of results:

- In Dhaka, Bangladesh with financial support of the Asian Development Bank and at a cost of several hundred million dollars, the entire water distribution network was replaced and restructured into 150 DMAs; this also included the replacement of all connections and consumer meters. As a result, physical losses reduced from 40 to less than 15%;

- The Nakuru, an NRW pilot focused on reducing commercial losses showed NRW to be more than halved (from 50% to 20%) within nine months, without any investment in network rehabilitation.

In any water utility there will always be some NRW. E.g. there are production losses, water is needed to clean pipes, and there will always be some water lost in the system. It should be noted that below a certain percentage NRW, the costs of further reducing NRW will exceed the benefits. At that point in the process it will not make sense to further try to reduce the level of NRW.

Literature:

Asian Development Bank on NRW: http://hdl.handle.net/11540/1003