For better understanding the position of women farmers vis-à-vis male farmers it is important to know the specific constraints of women farmers. Ester Boserup was one of the first to analyse this in her book “Women’s Role in Economic Development” (1970). She described the changes that occurred in traditional agricultural practices as societies became modernized. And in so doing she examined the differential impact of those changes on the work done by men and women.

Gender based labour division

The kind of women’s activities and the degree of women’s involvement in agriculture varies widely depending on culture, caste and class, agricultural production system, and -most importantly- the access to and control over resources. But wherever one goes, a gender-based labour division is often common, but hardly ever it is rigid, as it can change when circumstances and opportunities change. Labour division is often more flexible in practice than in people’s mind. Two examples:

- Albania 1995: In the context of a World Bank Irrigation Rehabilitation Program, an engineer explained that field irrigation was a task solely done by men. During a field visit a couple was observed jointly irrigating, i.e. opening and closing furrows. When asked about this, the engineer answered that the woman was ‘just helping her husband’; he did not acknowledge that also the woman was irrigating.

- In the project area of the Blue Gold Program in coastal polders in Bangladesh, tasks in the rice fields used to be mainly done by men. Improved water management and agricultural extension led to increased cropping intensities and higher yields, which required more labour. Technical Report 26 found that “women may now be hired for almost all farm operations, including transplanting and weeding paddy and the preparation of fish ghers (basins), and have to some extent replaced male wage labour”, the latter now being largely absorbed by non-farm employment. Blue Gold’s monitoring reports also demonstrate that all improved agricultural practices are adopted by both men and women farmers, though some more by men (such as Integrated Pest Management with 76% of the adopters being male) and others more by women (such as the used of improved chicken hatching practices with 92% of the adopters being women).

This means that gender based labour divisions should never be assumed but always be assessed, e.g. as part of a gender analysis.

Female farmers in different situations

Two main situations can be distinguished in the way female farmers work: (i) women who grow own crops and/or have own animals, whereas their husbands grow other crops and/or have other livestock (more common in Africa); and (ii) women who work in a ‘team’ with their husbands, jointly growing crops and jointly rearing livestock (more common in Asia). In practice there are many mixed situations, such as a female farmer being solely responsible for rearing poultry, whereas she works jointly with her husband in field crops. Moreover, the situation of women in smallholders’ households often differs from the situation of women in large landowners’ households.

In addition to female farmers, female wage labourers need to be acknowledged. They are often from poor and landless households, and work on other people’s farms or on commercial farms or estates. Women as agricultural wage labourers usually earn -considerably- less than male workers for the same amount of work.

Women farmers vs male farmers in the labour force

Worldwide women have always been actively involved in agricultural production. A recent CGIAR publication states that “women make up 43 percent, on average, of the agricultural labour force in low- and middle-income countries”. However, women’s participation in agricultural work differs across regions. A 1991 FAO publication by Vandana Shiva was titled “Most farmers in India are women”. World Bank’s World Development Report (WDR) of 2008 (on Agriculture and Development) stated that men and women in Africa work about equally in agricultural self-employment, whereas in Latin America and South Asia women work less than men in agricultural self-employment. But WDR 2008 also observed that in all these regions women have broadened and deepened their involvement in agricultural production in recent years. Agricultural production still is the most important livelihood and/or source of income for rural women in most developing countries.

There used to be the view that women’s agricultural activities focus more on feeding the families, whereas men would be more involved in cash crops. But with a growth of the ‘cash economy’ income generation has become more important for many female farmers. However, many female farmers are disadvantaged as compared to male farmers with regard to access to resources, including access to knowledge, services, credit, land and markets.

Women’s access to land

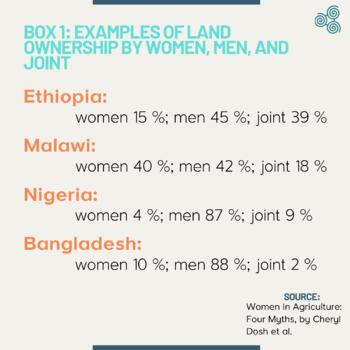

Both legal systems and patriarchal gender norms may prohibit or make it difficult for women to acquire or retain land. In addition, almost all inheritance systems disadvantage women in terms of land inheritance, and when women legally inherit, they often face strong social pressure to relinquish their inheritance. As a consequence, there are many countries where the proportion of land owned by women is substantially less than that owned by men. In this context, the proportion of land owned jointly by men and women, typically spouses, should also be taken into account.

Selected examples of ownership of household agricultural land are shown in box 1 above.

In a number of countries in sub-Sahara Africa, e.g. Kenya and Burundi, because of patriarchal norms and values and legal barriers, women farmers reportedly lost their access to land after the death of their husbands. The male members of the husbands’ family tend to claim the inheritance, including the land, leaving the widows and their children without any assets for their livelihoods.

Governments can play an important role in improving women’s access to land by designing and/or adjusting laws and regulations, as has shown in the example of Rwanda.

The adjustment of the inheritance law in 1999 gave men and women equal rights for inheriting land, which contributed to a more prominent role of women in agriculture. The Dutch Land Registration (‘Kadaster’) supported the regulation of Rwanda’s land registration system, which now promotes joint land titles, i.e. registering land ownership in the names of both husband and wife. This improved women’s access to financial and other resources. Together with other regulations, such as equal representation in parliament and at least 30% women in government employment, this led to a drastic change in the position of women in Rwanda during the course of one generation (post 1993).

Experiences have learned that increased agricultural production and household income do not automatically lead to increased food security. Enhancing women’s involvement in household decision making in combination with access to resources and information, e.g. on healthy nutrition, is also needed, see these two examples.

In the north west of Rwanda the commercial cultivation of potatoes and carrots as male cash crops replaced much of the vegetable cultivation for own consumption and for local sales. At local markets other vegetables than potatoes and carrots were hardly available anymore. As a consequence, people’s diets became unhealthy, leading to malnutrition. Stunting among children increased again.

In Bangladesh the EU found that food security projects increasing agricultural production and incomes did not lead to reduction in stunting among small children, whereas overweight and obesity among adults were on the increase: the double burden of malnutrition. Two main reasons were identified: (i) increased incomes were used to buy more ‘status food’, as ready-made sweets and snacks; and (ii) increased incomes led to the replacement of the standard diet for poor people consisting of rice, dal (lentils) and vegetables, by rice and animal proteins, such as fish or chicken, thereby reducing or omitting the consumption of vegetables. Local vegetables were often considered as poor-man’s food.

The limited access of women to resources and lack of participation in decision-making pose daunting challenges for female farmers to increase their productivity and income. These challenges are enhanced by the often dual (if not triple) burden of women by child bearing and unpaid care and domestic work (reproductive work).

Key constraints for women farmers

The most important constraints can be summarized as:

- Traditions, attitudes and prejudices against women's participation in the labour force outside the house.

- Legal barriers and (financial) illiteracy among women.

- The burden of unpaid care and domestic work, such as cooking, cleaning, childbearing and taking care of children, the sick and elderly. These time-consuming tasks are traditionally considered women’s responsibility in most societies, thereby limiting the time women can spend on productive work, community activities and leisure.

- Limited access to land, credit, agricultural equipment and technologies, extension service and market actors.

- Health burden due to frequent pregnancies and/or at a too young age (due to early marriage), work overload and malnourishment.

- Inadequate insights in gender issues within agriculture, limited implementation of existing gender equality policies and limited ability to develop agricultural policies and strategies that are also meeting the needs of women farmers.

- Lack of realization among policy makers that reducing gender inequalities and empowering women are essential for socio-economic development.

The slide in the above box presents barriers to the empowerment of women farmers as observed in the Blue Gold Program in coastal Bangladesh.

Invisibility: A special constraint has always been the invisibility of women farmers. The concept ‘farmer’ has had a male connotation for a long time; nobody envisaged women when talking about farmers. Many agricultural tasks that women used to do, such as post-harvest activities and homestead production, were often regarded as women’s domestic tasks, rather than as productive work. Last but not least, women often fulfilled (manual) tasks that were literally less visible, often also time-consuming, such as weeding, whereas men took-up more visible tasks such as mechanization, marketing and maintaining contacts with service providers. Also in statistics women’s role in agriculture has often been underrated, especially when only main occupations are reported. A woman spending daily 6 hours on agricultural work and 8 hours on domestic and care work will be classified as housewife; a man working 6 hours in agriculture, and doing no other work, will be classified as a farmer.

As a consequence of the ‘invisibility’ of women farmers, combined with traditional norms, they are often poorly reached by agricultural extension, as illustrated by this example from Ethiopia.

Agricultural extension in Ethiopia targets the male heads of households for their training and extension activities. The fact that most extension officers are male contributes to women farmers from female headed households being overlooked. Women farmers in male headed households are hardly recognised. The fact that only one person per household is allowed to participate in training activities, makes that in practice only men participate. As someone said: “Men are not willing to send their wives to extension training, as it would look bad upon them if they let their wives participate instead of themselves”.