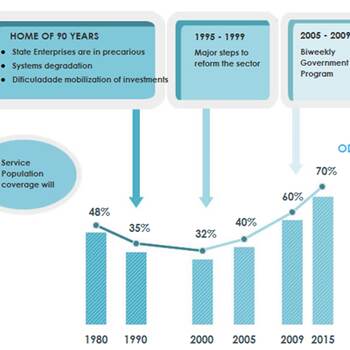

Situation at independence

At independence, central water supply was restricted to the ‘Portuguese’ part of the towns. Maputo and Beira were the only cities with sewered centres (‘cement city’). In rural areas, just 2% of the population had access to an improved water source. ‘Cattle of the Portuguese had a better water supply than most of the Mozambican population’ (quote Alvarinho TV interview 2017). The Portuguese had invested in dams for hydropower and irrigation; several of these works were still under construction at independence. The Portuguese hydrologic monitoring network had been rather good (quote interview Savenije 2022). With independence, most of the core staff for water services had left the country, however, and the new state had to find ways to overcome major challenges of staff shortage, maintenance, and expansion of services.

Policy trends

In the first fifteen years after independence, water and sanitation provision and water resource management were considered as a task of the state. Drinking water and sanitation were approached from a basic needs' perspective. The efforts to make new infrastructure was, however, counteracted by the decay of existing structures because of limited maintenance. This was the main reason for a policy shift that became apparent in the first Water Act in 1991 and Water Policy in 1995, which put more emphasis on decentralisation, deconcentration and private sector involvement. Wkith deconcentration is meant the delegation of power of the government institutions to (semi-)autonomous institutions or companies, which can be public or private.

The water development policies were influenced by the international agenda setting through the first Water Decade (80s). For Mozambique, this provided the opportunity to get assistance of UNDP and UNESCO to formulate their programmes and get additional technical assistance. Thereafter, policies were inspired by the neo-liberal privatisation concepts (from the 90-ties), public private partnership approaches (from 2000 onwards), the Millennium Development Goals (2000-2015) and the Sustainable Development Goals (2016-2030).

Water Resources

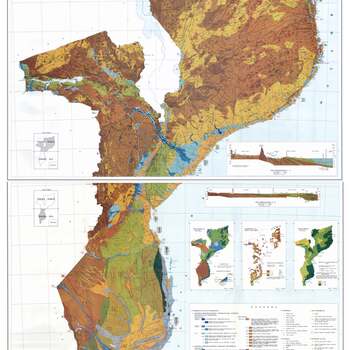

Mozambique is rrelatively rich in water resources, although there is geographical and seasonal variation. The amplitude of the variation is enlarged by climate change. Most of the surface water is coming from international rivers, being the Maputo, Umbeluzi, Incomati, Save, Pungue/Buzi, Zambeze/Chiure, and Rovuma rivers. Of the renewable water, almost 54% comes from abroad (AQUASTAT). The South (Maputo, Gaza, Inhambane) and West (Tete and parts of Sofala and Manica) are relatively dry. The hydrological year is characterised by one wet season (from October – April) and one dry season (from May – September).

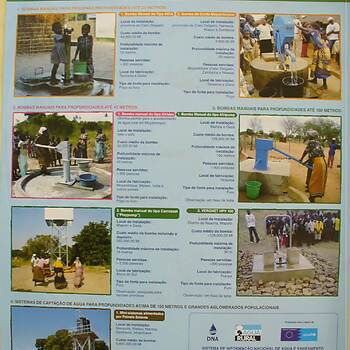

The South and the coastal areas are dominated by sedimentary basins with medium to good groundwater productivity. Some geological formations have brackish water, and over-extraction can lead to salinisation by seawater intrusion. Salinity is also a risk in the older inland sedimentary basins, including the area along the middle course of the Zambeze river. The Basement Rocks dominate in the inland areas in the Central and Northern part of the country and have limited groundwater productivity. Shallow wells can be made in many areas. Groundwater is the major source for most of the towns.

The earliest in-depth description of water resources in Mozambique was from 1987 and has a focus on groundwater (DNA 1987). A more recent description was published by GOM/DNGRH in 2017 as part of the SDG Action Plan, which was extended for WASH in 2018 (in Portuguese, only).

Natural disasters

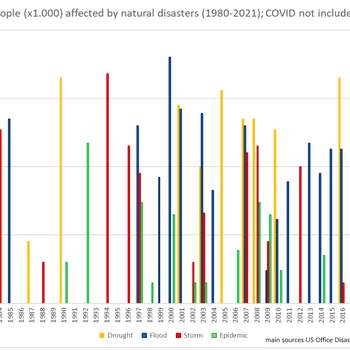

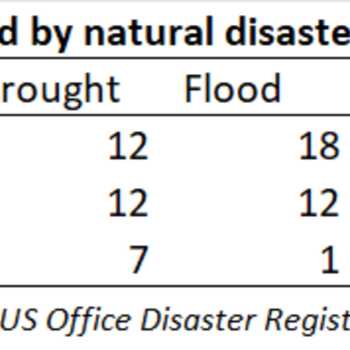

Mozambique is highly vulnerable for natural disasters like droughts, floods and tropical storms (Almeida 2018; UN Habitat 2023). It has rank 154 out of 185 rated countries in the Climate Vulnerability index of ND GAIN with a 0.493 rating for vulnerability and 0.263 for readiness (data 2021). A valuable risk map was made in 2015 by the UEM to analyse the risks for schools (UN Habitat 2023). Very severe were the droughts of 1979-1981 with high starvation, the Limpopo floods of 1977 and 2000, and the cyclones Domoina (1984) and Idai (2019) being the most devastating ones, till now. Climate change seems to increase the risk of cyclones (frequency and intensity). Increased temperatures give much higher evaporation than before and hence an increased water demand, especially in agriculture.

Prone to floods, cyclones, and droughts

Due to its position along the Madagascar Channel and Indian Ocean, Mozambique is regularly hit by tropical storms and cyclones (once in 3 years on average during the last 60 years). Highest probability (once in 2 years; 47%) is with the global phenomenon La Niña, especially when the average temperature in the Pacific is more than 1 degrees Celsius below average, otherwise it is once in 4 years (25%) (data analysis Bouman 2023). Some of the tropical storms have a serious impact on flooding, especially when they provide heavy rainfall in inland areas and neighbouring countries. A landfall of a cyclone does not necessarily have a devastating impact through heavy rainfall. The average number of affected people per year with a cyclone or flood is about halve a million. Starvation is generally limited and cannot be compared to the deadly impact of diseases such as malaria.

Interestingly, also drought probability is much higher with La Niña: 40% for years when the Pacific Ocean is more than 0,5 degrees below average, against 15% for years when the Pacific is more than 0,5 degrees above average (El Niño); and 33% for the years with more average temperatures (-0,5 to +0,5). Droughts can occur in the same year as cyclones. In general, droughts affect many more people than floods (average of 1.8 million people in a year with drought) over a much longer time span and with many more casualties.

Water demand

Water use is dominated by agriculture (73% in 2006), but still limited to 0.5% of the renewable water resources (AQUASTAT, data 2021). Potentially, an area of 30 times the actual surface can be used for irrigation (World Bank 2006; quoted in the Action Plan 2018, page 2634). Industry and energy require a lot of water, which can often be re-used in the system.

Globally, a country has water stress when it has less than 1,700 m3/cap/year of renewable water resources. Mozambique has about 7,000 m3/cap/year including the 54% that comes from neighbouring countries (see note 1). But there are geographical and seasonal differences.

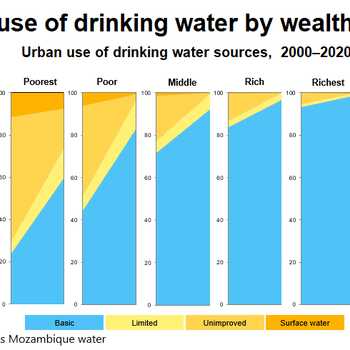

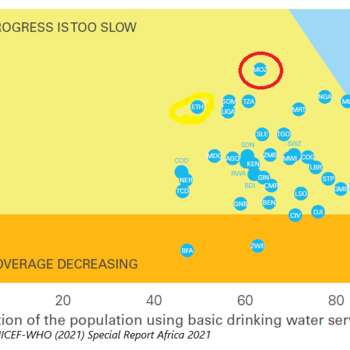

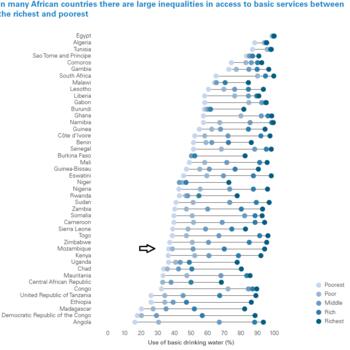

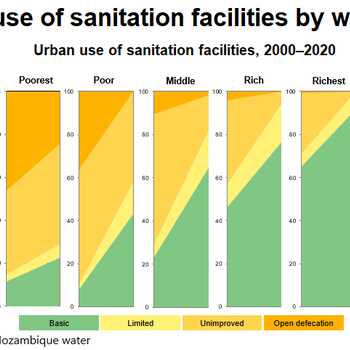

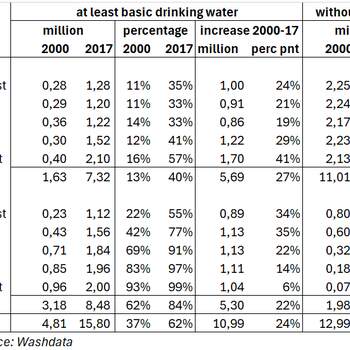

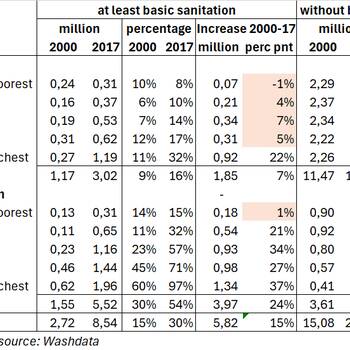

Water and sanitation access

For drinking water (and sanitation) the discrepancy in access is very high between large towns, small towns and rural areas, and between the lowest income quintile and the highest income quintile (UNICEF 2016; fig 27 and 29). Efforts are however more evenly spread for drinking water, both for rural and urban. Increase in access between 2000 and 2017 is rather similar in 9 out of the 10 income groups (see tables above). This contrasts with sanitation. Between 2000 and 2017, about 11 million people got new access to at least basic drinking water, but the number of people without access to at least basic drinking water hardly reduced (from 13.0 - 12.8 million people). For sanitation, these figures are worse, with a growth of people with access with 5.0 million, while also the number of people without access was growing with 5.1 million.

In 2020, Mozambique was among the countries with the lowest WASH coverage in the world, with 63% for water and 37% for sanitation at, at least, basic levels. World Bank 2018 makes a thorough analysis, while UNICEF is making annual budget analysis for the WASH sector, latest for 2019.

National Institutions

The Ministry for Public Works, Housing and Water Resources (MOPHRH) is responsible for water, while former names were MCA (Construction and Water) and MOPH. The Ministry is guided by a National Forum for water (before 2016 called National Water Council (CNA)), with representation of the sector and administrative layers.

Till 2017, water was dealt with by the National Directorate for Water (DNA). In 2017, DNA was split in DNAAS for drinking water and sanitation and DNGRH for water resource management. At provincial and district levels there are departments for (drinking) water and sanitation.

Decentralisation of water resource management

Decentralisation of water resource management started in 1991 with the adoption of the first Water Act and the creation of the first semi-autonomous Regional Water Resource Administration (ARA Sul). During the years five ARAs were created, starting from the South. In 2020 this was reduced to three: ARA Sul, ARA Centro and ARA Norte, while they got more autonomy as an Instituto Público.

Decentralisation and deconcentration in WASH in major towns

Decentralisation in drinking water and sanitation was first mentioned in 1995 in the first National Water Policy, which initiated a delegated management model for drinking water services by private operators. The World Bank has been pushing for this model to overcome the parallelisation of water services due to lack of revenues. For urban water supply, the deconcentration started in 1998 with the adoption of the Delegated Management Framework, the creation of FIPAG as asset, fund and contract manager for the larger towns and the installation of a regulator, CRA (later called AURA).

The concession contracts with private sector companies for the water service provision in the 5 main cities did not work out well, and FIPAG also assumed the role of operator, a task that was extended to more than 20 cities over the years. For Maputo there have been special arrangements till 2015.

Decentralisation and deconcentration of WASH in smaller urban centres

For most of the smaller towns another institution was created in 2009, called AIAS (Administração de Infra-struturas de Água e Saneamento), which is also incorporating drainage infra-structure for waste water in all urban centres, including Maputo. The aim is to apply commercial principles in the operation of services for which the contracting of private enterprises is the preferred model. In 2023, already 70 (of the 130) towns are served by private water operators. The legal aspects of AIAS were regularly updated, such as in 2009 and in 2020 (Decree 112/2020). By the end of 2020 a large concession was approved for 30 years with a foreign investor, called Operation Water Mozambique Lda (Decree 111/2020), but the investor has difficulties to source sufficient funding (situation mid-2023).

The ‘privatisation’ of water supply in Mozambique is critically followed by several scholars. A recent summarising analysis is written by Chris Büscher (Büscher 2024).

Small private operators

From 1995 onwards, many informal small water service providers (so-called ‘POPs’, Pequenos Operadores Privados) entered the market, especially in the outskirts of Maputo and Matola, where Águas da Região de Maputo is concession holder but not able to deliver. In 2018, USAID counted more than 1,800 of such small private operators, serving 1.8 million people. The majority of them iare operating in the South of the country. They received a lot of opposition from Águas da Região de Maputo, also because the water quality could not be guaranteed. By organising themselves and with a strong lobby, many of the ‘POPs’ have obtained a temporary semi-legal status (Ahlers et al 2013a; Ahlers et al 2013b).

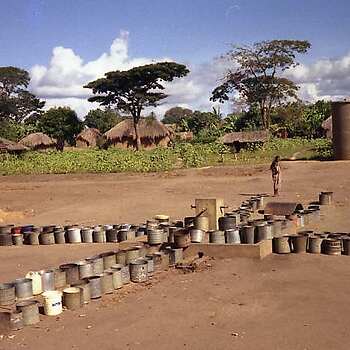

Rural Water and sanitation

For long, rural water supply and sanitation has been dealt with in special programmes under DNA (now DNAAS), working through the provincial and district departments for water and with special units (Estaleiros; EPARs) for construction and repair of water points. Awareness raising and education (‘animação’) and participatory approaches have been key, next to the use of appropriate technologies and Village level Operation and Maintenance models (Lamoree 1997). Over the years, this participatory part for water supply became outsourced, while for sanitation a modified version of the Community Led Total Sanitation approach was introduced.

This rural programme has had different names: Água Rural, PRONAR and PRONASAR. Now it has reached a stage of decentralisation. Since the early eighties, these rural WASH programmes are strongly backed by UNICEF.

Sanitation

With 37%, sanitation coverage is very low. Only some city centres have central sewerage and wastewater treatment is rare. Most of the sanitation is on-site, while open defecation is still widely practiced in rural and peri-urban areas (https://washdata.org).

Sanitation has been with several institutions. Initially, a low-cost sanitation programme was brought under the Ministry of Environment (MICOA, Instituto de Planeamento Físico) during which the famous Mozambican sanplat was promoted, a sturdy latrine slab with raised foot stands (e.g. Brandberg 1991, WRC 1998), which is manufactured in many small (private) workshops. Later, the sanitation programme was brought under DNA.

Urban sanitation was the responsibility of municipalities. But the Drainage of Maputo has remained with DNA (DNAAS) for long. In 2009, the management of infrastructure for urban wastewater drainage was brought under AIAS (GOM 2009 and GOM 2010). Separate strategies are developed for urban sanitation (2011) and rural sanitation (2021).

Parastatals

During the socialist period, there was one state drilling company (GEOMOC) and one state company for water equipment, and accessories (HIDROMOC), but after the liberalisation these state companies were dissolved.

Professional sector organisations

To have a better understanding between public and private parties in the water sector, the membership organisation PLAMA was created in 2012. Individual water professionals are active in the membership organisation Aquashare.

Relevant policies

After the first National Water Policy of 1995 there have been several updates, such as the National Water resource strategy in 2007, an urban sanitation strategy in 2011, a revised Water Policy in 2016, an action plan for the SDGs on water resources in 2017, and a revised one that is including WASH in 2018.

Resources and further reading

Ahlers, R., Schwartz K., Perez Guïda V. (2013).’ The myth of 'healthy' competition in the water sector: The case of small-scale water providers'. Habitat International, 38 (2013): 175-182

Ahlers, R., Perez Guïda V., Rusca M., Schwartz K. (2013). ’Unleashing Entrepreneurs or Controlling Unruly Providers? The Formalisation of Small-scale Water Providers in Greater Maputo, Mozambique'. Journal of Development Studies, 49 (4): 470-482

Almeida M.L.R.M. de (2018). ‘Mozambique’s disaster risk profile, a monographic issue’; in: Emergency and Disasters, Vol 5, Nr 2 2018; University of Oviedo

Bihat (2014). ‘Comparison of small-scale providers' and utility performance in urban water supply: The case of Maputo, Mozambique’; in: Water Policy16(1):102

Blanc A. (2012). 'The small-scale private water providers (SSPWPs) of Maputo: an alternative model to be encouraged?' In: Blanc A. and Botton S. (2012) Water services and the private sector in developing countries, Comparative perceptions and discussion dynamics; Section 3.6 page 371 – 391

Brandberg B. (1991) The SanPlat system;

Büscher Chris (2021). Water aid and trade contradictions: Dutch aid in the Mozambican waterscape under contemporary capitalism; PhD thesis University of London – SOAS

Büscher Chris (2024). ‘Expanding Water Privatization in Mozambique: Producing Success, Reproducing Neoliberal Water’; in: Development and Change (on behalf of Erasmus/International Institute of Social Studies/ISS; John Wiley and sons; open access

Chaponniere E., Collignon B. (2011). 'PPP with local informal providers aimed at improving water supply in the peri-urban areas of Maputo, Mozambique'; paper presented at 35th WEDC International Conference UK 2011

GOM (1979). Atlas Geográfico Volume 1; Ministério de Educação e Cultura; NICC E01142

GOM (1986). Atlas Geográfico Volume 1; 2a edição; Ministério da Educação; NICC E01143

GOM (1987). Hydrogeological map of Mozambique. Maputo: National Directorate for Water Affairs (Ferro, B.P.A. and Bouman D.); Map South with Legend; Map North; NICC E01127, E01128 and E01129

GOM (1991) ‘Lei de Aguas; Lei No 16/91 de 3 de Agosto’; in: Boletim da República, Número I- 31, 2o suplemento, 3 de Agosto de 1991

GOM (1991) ‘Criação das ARAs; Decreto No 26/91’; in Boletim da República, Número 272, Decreto No 26/91 de 14 de Novembro de 1991

GOM (1995). ‘Política Nacional de Águas’; in: Boletim da República, Número 34, Resolução No 7/95 de 8 de Agosto de 1995

GOM (1998a). ‘Cria base legal que permita a implementação de um Quadro de Gestão Delegado do Abastecimento de Água’; in: Boletim da República, Número 51, Decreto No 72/98 de 23 de Dezembro de 1998

GOM (1998b). ‘Cria o Fundo de Investimento e Patrimónió do Abastecimento de Água – FIPAG’; in: Boletim da República, Número 51, Decreto No 73/98 de 23 de Dezembro de 1998

GOM (1998c). ‘Cria o Conselho de Regulação de Abastecimento de Água – CRA’; in: Boletim da República, Número 51, Decreto No 74/98 de 23 de Dezembro de 1998

GOM (2003). ‘Regulamento dos sistemas públicos de distribuição de águas e de drenagem de águas residuais’ (technical standards and norms); in: Boletim da República, Número 26, Decreto No 30/2003 de 1 de Julho de 2003

GOM (2005). ‘Estatuto da Administração Regional de Águas do Zambeze’; in: Boletim da República, Número 12, Diploma Ministerial No 70/2005 de 23 de Março

GOM (2007a). ‘Política de Águas’; in: Boletim da República, Número 43, Resolução No 46/2007 de 30 de Outubro de 2007

GOM (2007a). ‘Aprova o Regulamento de licenças e concessões de águas’; in: Boletim da República, Número 43, Decreto No 43/2007 de 30 de Outubro de 2007, 5 o Suplemento

GOM (2007b). Estratégia Nacional de gestão de Recursos Hídricos; Relatório aprovado na 22a sessão do Conselho de Ministros de 21 de Agosto de 2007; 33 pages (Conselho de Ministros)

GOM (2007c). National Adaptation Programme of Action; prepared by MICOA for the UNFCCC, endorsed by the Council of Ministers on 4 Dec 2007

GOM (2009a). ‘Alargão âmbito de abrangência do quadro da Gestão Delegada do Abastecimento de Água aos sistemas públicos de distribuição de água e de drenagem de águas residuais’ (CRA); in: Boletim da República, Número 19, Decreto No 18/2009 de 13 de Maio de 2009

GOM (2009b). ‘ Cria a Administração de Infra-estruturas de Água e Saneamento’; in: Boletim da República, Número 19, Decreto No 19/2009 de 13 de Maio de 2009

GOM (2009c). ‘Aprova o Estatuto Orgânico da AIAS’; in: Boletim da República, Número 52, Resolução n.º 34-2009 de 31 de Dezembro de 2009, 10o suplemento

GOM (2009). Atlas de Moçambique; Editora Nacional de Moçambique e INDE

GOM (2010). ‘lista dos sistemas por resp de AIAS’; in: Boletim da República, Número 51 de 27 de Dezembro de 2010, Diploma Ministerial No 237/2010

GOM (2011). On: provincial delegations AIAS; in: Boletim da República, Número 45 de 14 de Novembro de 2011, Diploma Ministerial No 257/2011

GOM (2011). Estratégia Nacional de Água e Saneamento Urbano 2011-2025; MOPH, aprovada pelo Conselho de Ministros na 42a sessão de 22 de Novembro 2011

GOM (2015) ‘Aprova o Regulamento de Licenciamento de Serviço do Abastecimento de Água Potável por Forncedores Privados’; in: Boletim da República, Número 104, Decreto N.º 51-2015 de 31 de Dezembro_2015

GOM (2016). ‘Política de Águas’; in: Boletim da República, Número 156, Resolução No 42/2016 de 30 de Dezembro de 2016; https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/moz203194.pdf;

GOM (2017). ‘Regulamento do Uso e Aproveitamento de Albufeiras e Lagos’; in: Boletim da República, Número 10, Decreto n.º 29/2017de 14 de Julho de 2017;

GOM (2017). Action Plan of the water sector to implement the Sustainable Development Goals, Vol 1: Water Resources Management; MOPH/DNGRH,

GOM (2017). Baseline Report SDG 6.5 (DNGRH; in Portuguese); http://iwrmdataportal.unepdhi.org/country-reports (filter: Mozambique)

GOM (2018). ‘Plano de Acção do sector de Águas para implementação dos objectivos de desenvolvimento sustentavel 2015-2030’ (pagina 2623 – 2714; 92 pages); in: Boletim da República, Número 207, Resolução No 40/2018 de 24 de Outubro; Volume I Recursos Hidricos (pg 2623-2658); Volume II Abastecimento de Água e Saneamento (pg 2658 – 2709; anexos 2710-2714)

GOM (2019). Resultados do Censo 2017, Apresentação final (power point) (INE);

GOM (2020) Mozambique SDG 6.5 monitoring report 05.10.2010 (DNGRH); http://iwrmdataportal.unepdhi.org (filter: Mozambique)

GOM (2020). ‘Decreto das ARAs de fusão e autonomia’; in: Boletim da República, Número 160, Decreto l No 73/2020 de 20 de Agosto de 2020; https://www.dngrh.gov.mz/index.php/publicacoes/legislacao-dngrh/compendios/4-criacao-das-aras

GOM (2021). ‘Estratégia de Saneamento rural 2021-2030’; in: Boletim da República, Número 160, Resolução n.º 55/2021 4 de Novembro de 2021;

GOM (2022). iv recenseamento geral da população e habitação. 2017; indicadores sócio-demográficos; Moçambique (INE; table 14.7 on water and sanitation);

GOM (2023) Indicadores básicos de ambiente 2017-2021 (INE)

Lamoree G. (1997). Community management of rural water supply services in Mozambique: development process, issues, and directions; study paper

UNHabitat (2023). Building climate resilience in Mozambique; the case of Safer Schools;

UNICEF (2016) Mozambique 2016 WASH expenditure analysis

UNICEF (2019). The state of WASH financing in Eastern and Southern Africa, regional level assessment

UNICEF (2020) Budget Brief WASH – Mozambique 2019

USAID (2018) Rapid water and sanitation market assessment

WCR (1998). A Technical Guide for project 563: "SanPlat: A Simplified Latrine System for Rural and Informal Settlement Areas”; South Africa WRC Report No. 563/1/98 ISBN 1 86845 429 0

World Bank (2018). Findings of the Mozambique Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Poverty Diagnostic. Washington: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank

Websites:

Aquashare: https://www.aquashare.org.mz/

AQUASTAT (FAO) (e.g. water resources): http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/data/query/index.html?lang=en

DNAAS: https://dnaas.gov.mz/

DNHRH: https://www.dngrh.gov.mz/

Digital map of surface water: https://monitoriaavaliacao.dngrh.gov.mz/

INE (on Census and other statistical data): https://www.ine.gov.mz

Notre Dame/GAIN (climate vulnerability Index): https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/rankings/

PLAMA: https://www.plama.org.mz/

WHO/UNICEF (on WASH coverage): https://washdata.org/data/household#!/

Interviews:

Alvarinho (1): (2017; Port; 60 minutes); link not included because it appeared to have a virus

Alvarinho (2): https://youtu.be/GE_R4I5Klh0

https://sustainablewatermz.weblog.tudelft.nl/2017/02/09/technology-for-life-phd-honoris-causa-for-manuel-alvarinho/#more-1277

Savenije (min 9:51 – 16:00): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fF4cAaF-nTo&t=591

Note 1: 7,000 m3/cap/year calculated from 216,000,000,000 m3/yr. : 30,000,000 people; World Bank 2007; quoted in Plano Nacional de Recursos Hidricos 2019 – page 4-80

Version management:

Original text written by D. Bouman, November 2024