Slave trade

For more than a millennium, slave trade dominated the history of the East African coast and its interior regions. The impact of this trade was profound, especially in societies that were predominantly oral. When key individuals, such as knowledge carriers, were captured, centuries of tradition and wisdom could be lost. The trade also caused frequent clashes between neighboring communities, a reality documented by Sir John Kirk, who accompanied British explorer Dr. Livingstone on his Zambezi expedition from 1858 to 1863 (Bossenbroek, 2023).

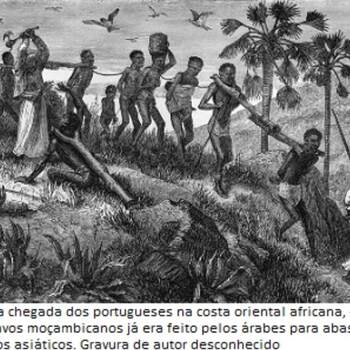

Arabic slave trade

From the 8th century, Arabs and Indians established trade relations with settlements along the East African coast. Zanzibar and Kilwa played dominant roles in this trade. However, the trade also spread along the Mozambican coast, particularly in Cape Delgado, where Ilha de Moçambique and Angoche were prominent sultanates (Lovejoy et al., 2021). Further south, (Nova) Sofala was already mentioned by the Oman writer Al-Masudi (10th century). Slaves were used to transport ivory and gold from the interior to the coast, after which they were shipped across the Indian Ocean. Ironically, Mozambique was named after Ali Mussa Mbiki, an early Arabic slave trader who ruled Ilha de Moçambique (Wikipedia).

An estimated 200 people per year were traded along the Swahili coast, with a peak of 3,000 to 6,000 per year in the second half of the 17th century, when the Sultanate of Oman dominated the Arabic slave trade, with Zanzibar as the main trading center (Vernet T., 2009).

Portuguese slave trade

Portuguese occupation began after Vasco da Gama’s first landing in 1498, but Portuguese control remained confined to coastal enclaves such as Nova Sofala (1502), Ilha de Moçambique (occupied in 1506), and settlements along the Zambeze Valley, notably Sena and Tete. The peak of Portuguese involvement in the slave trade occurred in the 19th century, with approximately 400,000 people from the Mozambican coast and the Zambeze Valley being forcibly taken during this period (Lovejoy E.B., 2020). Most were sent to the Americas to work on plantations.

Regarding the transatlantic slave trade, the Portuguese and their Brazilian successors were the largest slave traders, transporting 5.85 million people out of a total of 12.52 million. Of this, 0.54 million came from Southeast Africa and Indian Ocean islands (Slavevoyages). Though less documented, it is believed that a comparable number (about 14.5 million) was traded across the Indian Ocean, with 2 million coming from the Swahili Coast (Bossenbroek, 2023, p. 23, note Proloog/24).

In 1822, Portugal was one of the first European countries to begin halting its slave trade, although initially limited to its colonies in India (Eveline Dias, interview, Lisbon-based association of Afro-descendants DJASS). But Portugal was one of the last European countries to fully stop the slave trade, finally ceasing it in 1866, with a three-year transition period.

Role of the Dutch in slave trade

The Dutch also engaged in the slave trade from Mozambique, though in smaller numbers. Of the 63,000 slaves traded into ‘Dutch’ Cape Town, approximately 16,500 (26.1%) came from the African mainland, while Madagascar was the primary source of slaves(South African History on-line/SAHO).

In the transatlantic slave trade, the Dutch were responsible for about 10% of the Portuguese volume. Initially, the Dutch did not participate in the slave trade due to religious reasons. However, by the 18th century, a reinterpretation of the Biblical curse of Ham (Noah’s son, who was considered the ancestor of Africans) gave rise to a more active role in the independent trade of African slaves by the Dutch (Flinkenflögel, cited by Hartigh S. de, 2008, p. 24). They even believed that they were doing Africans a favor by freeing them from what they saw as violent and absurd African societies (Emmer 2000, cited by Hartigh S. de, 2008, p. 24).

References/Further Reading

Bossenbroek M. (2023). De Zanzibardriehoek, een slavernijgeschiedenis 1860-1900 (historical novel with many footnotes)

Flinkenflögel (1994) Nederlandse slavenhandel 1621-1803, page 88-94

Hartigh S.de (2008). Rotterdam and the transatlantic slave trade, pg 24, Erasmus Universiteit, quoting Flinkenflögel (1994) Nederlandse slavenhandel 1621-1803, page 88-94) and Emmer P.C. (2000) De Nederlandse slavenhandel 1500-1850, page 33.

Lovejoy P.E. (2000) Transformations in slavery: a history of slavery in Africa (revised edition); Cambridge University Press

Lovejoy H.B., Lovejoy P.E., Hawthorne W., Alpers E.A., Candido M., Hopper M.S., Lydon G, Kriger C.E, Thornton J. (2021). Defining Regions of Pre-Colonial Africa: A Controlled Vocabulary for Linking Open-Source Data in Digital History Projects

Slavevoyages: table with estimated number of slaves traded by countries , consulted 21/3/2023

Original version: 20/12/2024 D. Bouman