The rainy season of 1999/2000 brought heavy rains across Southern Mozambique and the surrounding areas, causing unprecedented flooding of the Limpopo River and several others. This disaster affected 4.5 million people and resulted in 800 deaths (Almeida, 2018). Mozambique organized a massive emergency response, alongside international rescue and humanitarian aid organizations (Hanlon and Christie, 2002).

Funding boost

This joint response to the floods and the urgent need for reconstruction accelerated the decision of donors to grant Mozambique debt relief under the IMF Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative. It also led to the provision of general budget support, strongly advocated by Dutch Minister Eveline Herfkens. Despite early warnings of corruption, including the deaths of a journalist and a banker who exposed corruption, donors proceeded with substantial financial aid, often with limited external oversight.

Politics

FRELIMO managed to remain in power at the national level, forming a political elite that benefited from the economic growth between 2001 and 2014. Systems were put in place to protect the interests of the political elite, and most top positions in institutions were held by party affiliates (Büscher, 2021). Decentralization efforts were designed in a way that allowed central control to persist, even in municipalities and provinces governed by the opposition.

Economic development

From 2000 to 2014, Mozambique experienced steady economic growth, with GDP per capita rising from around $200 to $600. This growth was driven by the country’s stability, debt relief, foreign investments, and the development of the extraction industry. The increase in GDP led the Dutch Government to anticipate that Mozambique would soon achieve middle-income status.

However, by 2014, economic prospects began to deteriorate. The Commodity Crisis that year affected the entire Sub-Saharan region, but the most dramatic blow came with the discovery of the Hidden Debt scandal in 2016. Mozambique had incurred $2.2 billion in debt to purchase arms and fishing boats without parliamentary approval, and funds from Swiss and Russian banks were illegally channeled. In response, the IMF and many donor agencies froze their support to Mozambique, particularly the funding funneled through the Central Government’s bank account. Some donors pulled out entirely, while others shifted to project- and program-based support, bypassing the central state budget.

External Setbacks

Further setbacks included natural disasters. The 2018 Cyclone Idai devastated Beira, causing an estimated €600 million in economic losses. The economy was further paralyzed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and rising prices followed the onset of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Mozambique’s prospects for fossil fuel exploitation also declined, with reduced coal exports due to decreased demand and delayed gas projects owing to security concerns.

Wealth disparity

The neo-liberal agenda and privatization continued, but corruption remained poorly controlled, and wealth inequality grew. A UN-Habitat study on Beira’s purchasing power between 2008/09 and 2014/15 revealed that the income disparity between the wealthiest and poorest quintiles worsened, with the ratio rising from 6.7 to 12.9. The 2019/20 Household Budget Survey by the Mozambican Institute of Statistics (INE) revealed a significant increase in poverty, with the national poverty rate rising from 48.4% in 2015 to 62.8% in 2020 using the $1.90 per day threshold. The poverty rate increased from 63.7% to 74.4% using the international $2.15 per day threshold (World Bank Group, 2023).

Critical voices

Many former supporters of socialist Mozambique have turned into very critical followers, one of them being Joseph Hanlon. But there are also critical voices within the country, such as that of the Instituto de Estudos Sociais e Económicos (IESE).

No economic miracle

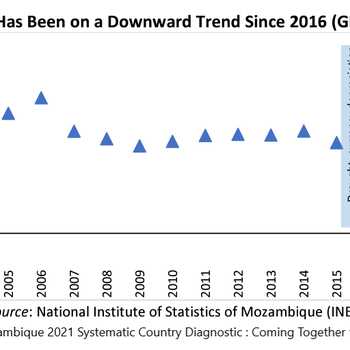

Despite being frequently cited as an example of economic progress by donors, Mozambique's economic data tells a more complex story. While GDP growth reached 8% in some years, the gap between Mozambique’s GDP growth and the average of other African countries is substantial when expressed in absolute figures. For instance, 8% growth from $300 per capita is less significant than 8% growth from $600 per capita. Moreover, GDP growth did not translate into increased income for the majority of the population. Instead, urban and political elites benefited most from the economic expansion, which was largely driven by industrial (aluminum) and mining (coal and gas) sectors (Cunguara, 2012). By 2015, GDP growth had slowed and became negative during the COVID-19 pandemic years (World Bank, 2022).

UN agenda of MDGs and SDGs

In 2000, the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were introduced, aiming to reduce the number of people lacking access to basic services. Mozambique took time to align with this global agenda and establish monitoring systems. A baseline report was published by the UN in 2002, and a final report from the Ministry of Economy and Finance followed in 2015. Key areas of concern under MDG 1 (child malnutrition), MDG 5 (maternal mortality), and MDG 7 (household access to improved water and sanitation) showed only limited progress, with only three sub-indicators meeting the targets: MDG 1 (prevalence of underweight children), MDG 3 (gender parity index), and MDG 4 (infant and child mortality rates). Seven other indicators showed progress.

In 2015, the MDGs were replaced by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), to which Mozambique responded more promptly. The Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE) now regularly publishes reports on the country’s progress toward these goals.

References/Further reading:

Almeida M.L.R.M. de (2018). ‘Mozambique’s disaster risk profile, a monographic issue’; in: Emergency and Disasters Vol 5, Nr 2 2018; University of Oviedo

Batley R. L. Bjornestad, A. Cumbi (2006). Joint evaluation of General Budget Support 1994-2004; Mozambique Country Report; University of Birmingham/IDD

Büscher C. (2021) Water and Trade contradictions; Dutch Aid in the Mozambican waterscape under contemporary capitalism; SOAS, University of London; pages 70

Cunguara B. (2012). 'An exposition of development failures in Mozambique'; in: Review of African Political Economy, Vol 39, No. 131. March 2012 pg. 161-170

GOM (2015). Booklet, Millenium Development Goals Indicators; Ministry of Economics and Finance

Hanlon, Joseph and Christie, Frances (2002). ‘Preparedness pays off in Mozambique’. In: ed. World Disasters Report 2002. Geneva: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies; only digital abstract

Hanlon, J. (2017). 'Following the donor-designed path to Mozambique's US$2.2 billion secret deal'. Third World Quarterly 38 (3): 753-770

UNHabitat (2020). Financing for Resilient and Green Urban Solutions in Beira, Mozambique (part of FRUGS)

WTO (2017). Trade Policy Review - Mozambique 2017

World Bank (2022). Mozambique 2021 Systematic Country Diagnostic: Coming Together for a Better Future

World Bank (2023) World Bank Group in Mozambique; fiscal years 2008-2021

World Bank Group (2023). Country partnership framework for the Republic of Mozambique for the period FY23-FY27; Report 176672-MZ

websites/data

- INE (Instituto Nacional de Estatistica): census and other data

- Wikipedia: number of IDPs

- World Bank: all kind of stats

Original version: 20/12/2024 D. Bouman