General Dutch-Mozambican cooperation – more than Maputo

The Dutch bilateral cooperation in the water sector in this period is described in a IOB working document/case study report (IOB 2000/Rodts).

With the Rome Peace Treaty of 1992, the Dutch government decided to focus on humanitarian aid for resettlement and demining. From 1995 onward it put priority on decentralised programmes with a rural focus (GON 1998), following the decentralisation efforts of the Mozambican Government, such as expressed in the Water Act of 1991. The central provinces of Zambezia and Nampula were selected. These densely populated provinces had been severely affected by the internal war and had a strong RENAMO basis. It was thought that development could bring more stability. The cooperation could also build on earlier aid provided to UNICEF for rural WASH in the Zambezia province.

In 1995, the Embassy in Maputo got a higher status and a larger mandate. Hence, it was able to assume its coordination role, which was shared with the Eduardo Mondlane Foundation before. It also took the responsibility to lead the donor coordination on water resources, but the related working group did only meet three times in the end 90s (IOB 2000/Rodts). The coordinating role continued for decades, and also included that for Rural water supply for some period. The Dutch Government was looking for modalities in which it did not have to work through the Mozambican government that was increasingly seen as an obstacle. The ‘cooperantes' model for Technical Assistance was partly kept in place, while SNV was invited to take over some of the ‘bilateral expat’ duties in the Nampula Province.

A major shift was made in 1999 after the visit of Minister Eveline Herfkens. This visit led to the end of the dominance of the ‘cooperantes' model, a reduction of project financing, the introduction of budget support and of debt-relief.

More support to the North

From its new ‘rural’ focus the Netherlands started to support the rural WASH programme PRONAR in Zambezia and Nampula with 4.6 million Euros. It also started the Support Unit Region North (SURN) for the Institutional support to the main urban water authorities in Nampula, Niassa and Cabo Delgado. Maximum budget was 1.5 million Euros. After a review, the original SURN project was replaced by the SAS project (Sistemas de Aguas Sustentaveis) in 1997. The SAS project intended to develop institutional models and capacity building for the urban systems in the North, except for the capital cities Nampula and Pemba. These two were planned to become integrated in the concession contracts under World Bank funding. The SAS project included works in the main towns Angoche, Ilha de Moçambique and Lichinga and three smaller systems in Malema, Ancuabe and Metangule. The core project team consisted of Dutch experts, contracted by the Embassy. The agreed maximum grant was 5.0 million Euros.

The external evaluation of the SAS project in 2001 concluded that, despite some concrete outputs, the project had the project had hardly invested in learning and dissemination, and it had been unable to test a model with more private sector involvement. There was no real receptive attitude towards private sector involvement in the utility services and all relevant private partners were based in Maputo (A.Makhoka 2002 of World Bank WSP; only draft available) [LINK]. It was recommended to integrate the further development of the private sector model in the Budget Support programme under design, which did not really happen. In fact, the change to water sector budget support was contrary to the intended decentralisation and deconcentration.

Initial institutional reforms Water Resource Management

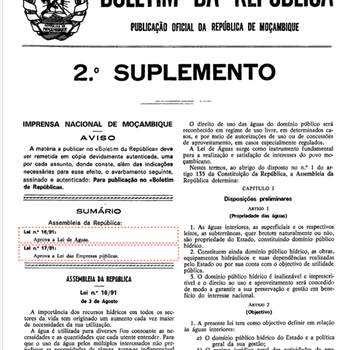

In the 90s, the Technical Assistance through ‘cooperantes’ in the institutions continued as before. Dutch expats have been rather influential towards the early institutional reforms in water resource management, such as defined in the Water Act of 1991, and the model of regional water administrations (ARAs).

The first ARA was created in the South (ARA Sul) and received institutional support by the Netherlands (1996 – 2000 with 2,2 million Euros), while a parallel project provided support to the creation of the other ones (1996- with 3,5 million Euros). The legal reforms for the creation of regional Water Authorities were among the first on the continent, but the full implementation took decades (Alba et all 2016).

Urban Rehabilitation Facility

To rehabilitate the urban water supply infrastructure after the Peace Treaty, the Netherlands created a Rehabilitation Facility. Originally, NGOs could apply for funding with a maximum of 90,000 Euros (200,000 Dutch guilders). Initially these were UNICEF, MSF, CARE, Red Cross and 2 Swiss NGOs. Despite of the fact that an external evaluation criticised the sustainability of the works, the Facility was continued with a higher maximum per project (220,000 Euros), but with a focus on Nampula. In total 4.9 million Euros was provided in 4 phases that lasted till 1996 (IOB 2000/Rodts).

Initial institutional reforms for (urban) Water Supply

In 1992, the Dutch Government had ended the support to the unit for water and sanitation at DNA (UDAAS) but continued with a more individual Technical Assistance to its successor (DAS). Dutch experts were also involved in the design of the first National Water Policy of 1995, that provided alternatives for the UDAAS model and would work towards a model with private sector involvement through Public Private Partnerships. The Embassy had already supported two important consultancy studies that aimed to prepare the ground for the privatisation of water supply operations in the first 5 (to 10) cities. The latter was further taken by the World Bank in the National Water and Sanitation programme II, 10% of the budget being covered by the Netherlands. The introduction of concession contracts for the main cities was warmly welcomed by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This is rather evident in a publication of the Communication department of the Ministry (GON 1998).

This new focus overruled the other urban initiatives of the 90s, such as the mentioned urban projects in Nampula and the ‘Rehabilitation Facility’ to support the most essential repairs to keep the water running.

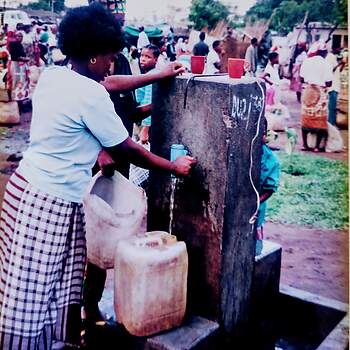

In parallel to the bilateral funding, there were also other Dutch actors supporting the urban water sector. One of them was the cooperation between the Water Company of Amsterdam and that of Beira; a twinning that was lobbied for by the Eduardo Mondlane Foundation. [see the poster of a fund-raising campaign].

Rural WASH

The reforms in rural WASH were just gradual and the PRONAR programme continued as before, with UNICEF in a rather dominant position. The Village Level Operation and Maintenance (management) concept was introduced, together with water fees to cover Operation and Maintenance costs (GON 1998). In 1997, PRONAR was reintegrated in the DNA structure, alongside with the DNA department for Water and Sanitation (DAS; IOB 2000/Rodts).

Sanitation

The Dutch support to the sanitation in Beira continued in the 90s, consisting of funding of pumping stations (around 0.9 million Euros) and technical assistance to the entity responsible for the operation and maintenance of the sanitation infrastructure: SSB (Serviço de Saneamento de Beira). An attempt to bring it under the Water Company failed and the Municipality took it back in 1993. Conclusions of an evaluation in 1997 were dramatic (IOB 2000/Rodts).

In 1992, the Netherlands started to support the Low-cost sanitation programme, with components under UNDP/UNICEF and the Mozambique Government. An evaluation in 1998 led to the plan to transfer the co-ordination from a project coordination unit to a department of DNA and to use the decentralised authorities for implementation, while promoting private sector involvement.

University cooperation

The cooperation between TU Delft and the Engineering Faculty of the Eduardo Mondlane University (UEM) started in 1987 in the Water Resource Engineering Cooperation programme, which ran till 1998. Although the first phase of this cooperation had also the character of ‘filling the gaps’ (SAWA 1992/Bouman); the next phases became more focused on setting up a sub-faculty for hydraulic engineering. The UEM finally decided to abandon the idea of a sub-faculty and to stay with a wider civil engineering faculty, because the student basis for such a separate sub-faculty remained small (IOB 2000/Rodts).

References

Alba, R. and Bolding, A. (2016). ‘IWRM Avant la Lettre? Four Key Episodes in the Policy Articulation of IWRM in Downstream Mozambique'; In: Water Alternatives, 9 (3): 549-568

GOM (1991) ‘Lei de Aguas; Lei No 16/91 de 3 de Agosto’; in: Boletim da República, Número I- 31, 2o suplemento, 3 de Agosto de 1991

GOM (1995). ’Política Nacional de Águas’; in: Boletim da República, Número 34, Resolução No 7/95 de 8 de Agosto de 1995

GON (1998). Hulp in Uitvoering – Drinkwater & sanitatie en ontwikkelingssamenwerking; (MFA; chapter 2 Drinkwater en sanitatie (pg 23-40); chapter 3: Mozambique (pg 41-54)); NICC E01149

IOB (2000). Netherlands support to the water sector in Mozambique: evaluation of sector performance and Institutional Development (Working paper as input for IOB No 284, written by Rodts R.P.A.; especially pages 29-33); no digital copy; NICC A09407; A10388; E01124

SAWA (1992). Evaluation Report Inter Institutional Cooperation between Eduardo Mondlane University and Delft University of Technology, Water Resources Engineering Project (WRE Phase II) 1990 – 1992; for NUFFIC; (Bouman D/SAWA; Lopes Pereira A./Consultec)

GOM (1991) ‘Criação das ARAs’; in: Boletim da República, Número 272, Decreto No 26/91 de 14 de Novembro de 1991

GOM (1998a). ‘Cria base legal que permita a implementação de um Quadro de Gestão Delegado do Abastecimento de Água’; in: Boletim da República, Número 51, Decreto No 72/98 de 23 de Dezembro de 1998

GOM (1998b). ‘Cria o Fundo de Investimento e Patrimónió do Abastecimento de Água – FIPAG’; in: Boletim da República, Número 51, Decreto No 73/98 de 23 de Dezembro de 1998

GOM (1998c). ‘Cria o Conselho de Regulação de Abastecimento de Água – CRA’; in: Boletim da República, Número 51, Decreto No 74/98 de 23 de Dezembro de 1998

Version management:

Original text written by D.Bouman, September 2024